One Child Nation Parent Guide

A searing documentary that looks at the personal and societal costs of China's three decades of forced family planning.

Parent Movie Review

Looking back on her decades of midwifery in China, Huaru Yuan confesses that she has no idea how many live babies she delivered, but she counted the 50,000 abortions and sterilizations she performed – many on unwilling patients – out of guilt. “Many I induced alive and killed. My hands trembled doing it,” she says. Now retired from midwifery, she focuses exclusively on the treatment of infertility. “I want to atone for my sins,” she says flatly, “for the abortions and killing I did.”

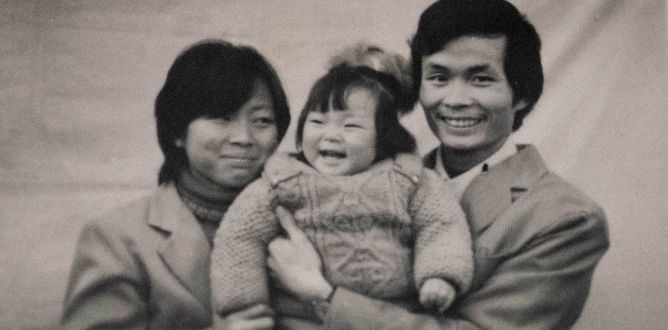

One Child Nation is a searing documentary, directed and narrated by Nanfu Wang, who was born in China in 1985, a mere six years after China implemented its draconian One Child Policy, which forcibly limited family size. Wang grew up in a culture permeated by propaganda and family planning slogans. She believed what she was taught – without checks on population growth, famine and cannibalism would ensue. Limiting family size would make China more powerful, prosperous, and peaceful. But after Wang moved to the United States and had her first child, she re-examined her early experiences: “I wonder if the thoughts I had were really my own or if they were simply learned.” In a quest to find answers to this question, Wang heads back to China with a camera crew and a desire to learn more about the policy that shaped her homeland’s culture for thirty years.

She begins with her own history. Her own name reflects her parents’ disappointment in having a daughter. “Nanfu” comes from the Chinese words meaning “man” and “pillar” and expresses the hope that this daughter will be as strong as a man. Luckily for Wang’s parents, their rural district allowed parents with a firstborn daughter to try again for a son, which they had five years after her birth. But governmental policy and cultural misogyny followed this birth as well: a basket was put in the living room by Wang’s grandmother who threatened to discard the baby if it’s female. And it turns out there’s more – Wang ‘s own family history has stories of abandonment or the sale of girl babies to traffickers, in the grim calculus that either option provides better odds of survival than infanticide at the hands of a disappointed grandmother or ruthless midwife.

Wang doesn’t shrink from the violence, pain and death that the One Child Policy caused. As one celebrated family planning official says, after discussing forced abortions and the women who cried, cursed, fought, and went insane: “It was like fighting a war. Death is inevitable. We were fighting a population war.” Others are less sanguine but more fatalistic. Over and over again, Wang’s interview subjects remind her that it was government policy. They didn’t want to inform on pregnant neighbors or help destroy their homes. But, in the face of government edict, what could they do?

This question is one of the most powerful questions in the movie. How could millions of people cooperate with a brutal policy that overturned a profound cultural commitment to families? But as Wang observes late in the film, “When every major life decision s made for you, it’s hard to feel responsibility for your choices.”’

One Child Nation tells a powerful national story on a personal level. But its greatest weakness is that it is unable to provide a more comprehensive look at its subject. While Wang does a fine job of showing the personal suffering of the policy and exploring the trafficking and sale of baby girls on the international adoption market, she does not mention the massive demographic dislocation caused by the preference for sons when family size is forcibly limited. Demographers suggest that one-fifth of Chinese men will be unable to find wives, a problem that is already leading to the kidnapping and trafficking of women. And the shortage of women is contributing to a rapidly falling birthrate which has dire consequences for future economic growth. Since these demographic issues are critical factors behind China’s scrapping of the policy in 2015, their omission from this production is significant.

Parents or teachers considering this movie for family or classroom viewing should know that One Child Nation does not take firm sides in the ongoing culture war over abortion. Rather, it gives both sides something to think about. From a pro-life perspective, the movie clearly depicts the horror of ending lives in the womb. And the scenes of dead babies in garbage dumps or preserved in glass jars of formaldehyde are heartbreaking. From a pro-choice perspective, the denial of women’s bodily autonomy is equally disturbing, with pictures of women tied up before undergoing forced medical procedures. As Nanfu Wang says, “I’m struck by the irony that I left a country where the government forced women to abort, and I moved to another country where governments restrict abortions. On the surface, this seemed like opposites. But both are about taking away women’s control of their own bodies.” Whatever moviegoers believe, this is a film that will spark discussion about a painful topic.

Directed by Nanfu Wang. Starring Nanfu Wang, Jiaoming Pang, Brian Stuy. Running time: 88 minutes. Theatrical release August 9, 2019. Updated October 1, 2019Watch the trailer for One Child Nation

One Child Nation

Rating & Content Info

Why is One Child Nation rated R? One Child Nation is rated R by the MPAA for some disturbing content/images, and brief language

Violence: There is no violent action on screen but violence is a frequent topic of discussion. People talk about forced abortions and sterilizations. Women are shown abducted and tied up before undergoing the procedures. Dead babies are shown in garbage dumps. Dead babies are shown in bottles of formaldehyde. There are paintings of aborted fetuses. People talk about having houses destroyed by the government as punishment for having additional children. People talk about killing or abandoning babies. There is discussion of selling babies to traffickers.

Sexual Content: None noted.

Profanity: Two sexual expletives are used in the film.

Alcohol / Drug Use: A person is shown smoking.

Page last updated October 1, 2019

One Child Nation Parents' Guide

What do you think of China’s One Child Policy? Do you think coercive measures were necessary to reduce population growth or do you think education and economic growth would have been equally successful? Is it always desirable to reduce population growth rates?

Wikipedia: One-child policy

The New York Times: One-Child Rule is Gone in China, but Trauma Lingers for Many

BBC: “Remarkable” Decline in Fertility Rates

The one child policy, when combined with strong prejudices against daughters, has created a demographic crisis in China:

Washington Post: Too Many Men

The Guardian: The impact of China’s one-child policy in four graphs

CNN: China faces unstoppable population decline by mid-century

The New York Times: China Will Feel One Child Policy’s Effects for Decades

Time: A Shortage of Women in China has Led to the Trafficking of “Brides” from Myanmar

CNN: China Ends One-Child Policy, Allowing Families Two Children

The Guardian: Can China recover from its disastrous one-child policy?

Washington Post: Beijing’s one child policy is gone. But many Chinese are still reluctant to have more.

The Atlantic: Why the One Child Policy Has Become Irrelevant

The Guardian: China’s lost little emperors…how the one child policy will haunt the country for decades

Time: China’s One-Child Policy: Curse of the Little Emperors

NPR: China’s Little Emperors Lucky, Yet Lonely in Life

Loved this movie? Try these books…

For a comprehensive look at the One Child Policy, you can read Tyrene White’s China’s Longest Campaign: Birth Planning in the People’s Republic, 1949-2005.

The cultural, economic, and personal costs of the policy are told in Mei Fong’s One Child: The Story of China’s Most Radical Experiment.

What happens when you create an entire society composed of “only children”? China’s “Little Emperors” have reshaped the culture and that phenomenon is explored by Xinran in Buy Me the Sky: The remarkable truth of China’s one child generations”.

The stories of abandoned, trafficked, and adopted girls from China is told by Kay Ann Johnson, an American who adopted a Chinese daughter. China’s Hidden Children: Abandonment, Adoption, and the Human Costs of the One Child Policy is a detailed study of this painful story.

Among the Hidden begins a fictional series by Margaret Peterson Haddix. Set in a dystopic future, these novels imagine a world where families are only allowed to have two children. Luke, an illegal third child, must live in hiding.

“What could I do?” is a common question in One Child Nation. But some people refuse to go along with things they see as morally wrong or unjust. To learn more about what motivates them, read Eyal Press’s fascinating non-fiction book, Beautiful Souls.